Browser not supported.

We support all latest versions of Chrome, Safari, Firefox and Edge.

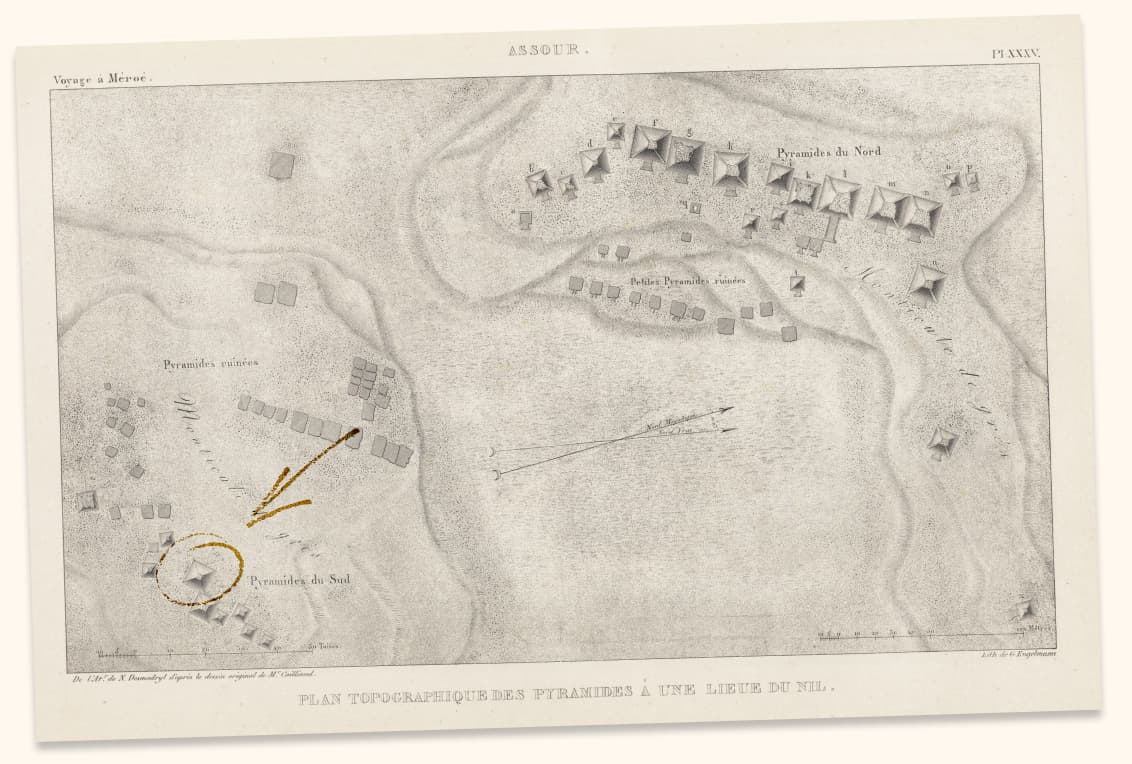

Explore Sudan’s Pyramids of Meroë

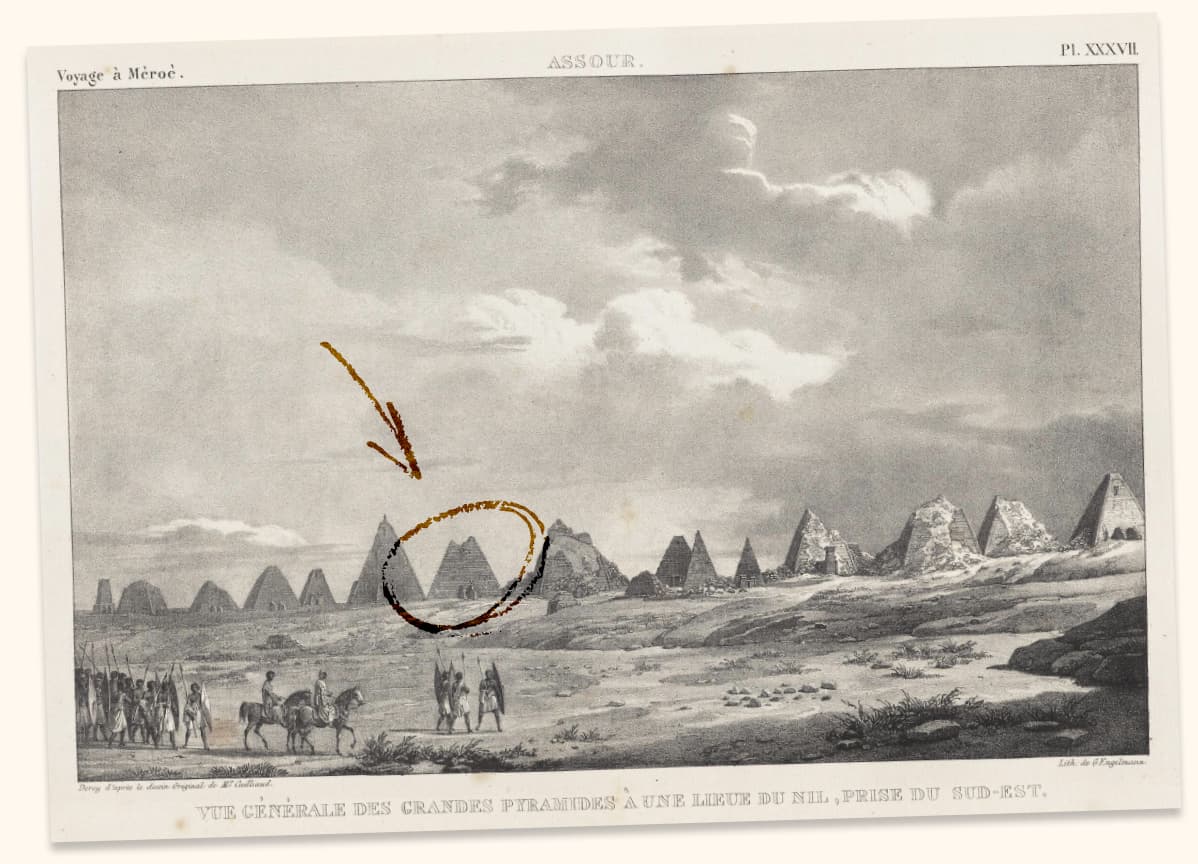

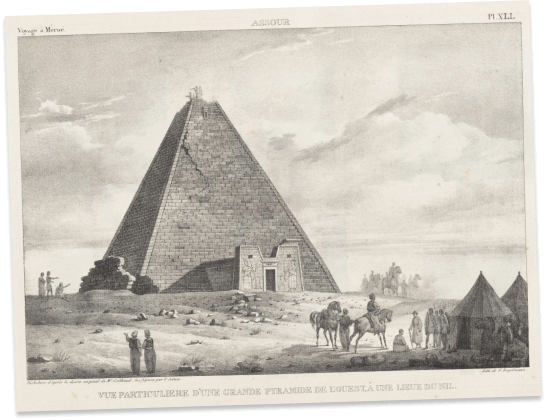

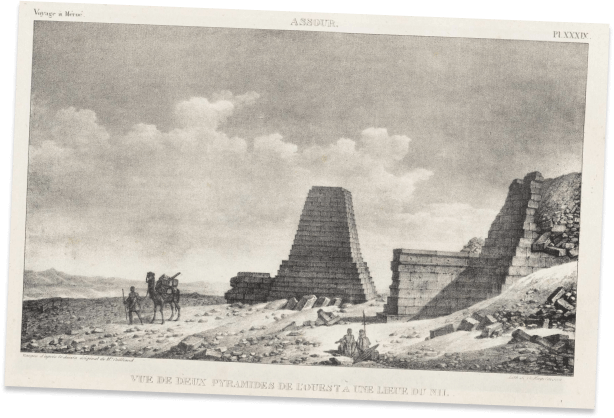

Uncover a city with over 200 pyramids. This is Meroë, the ancient capital of the Kushite Kingdom, in Sudan’s Nile Valley.

Alternatively, listen to the

The

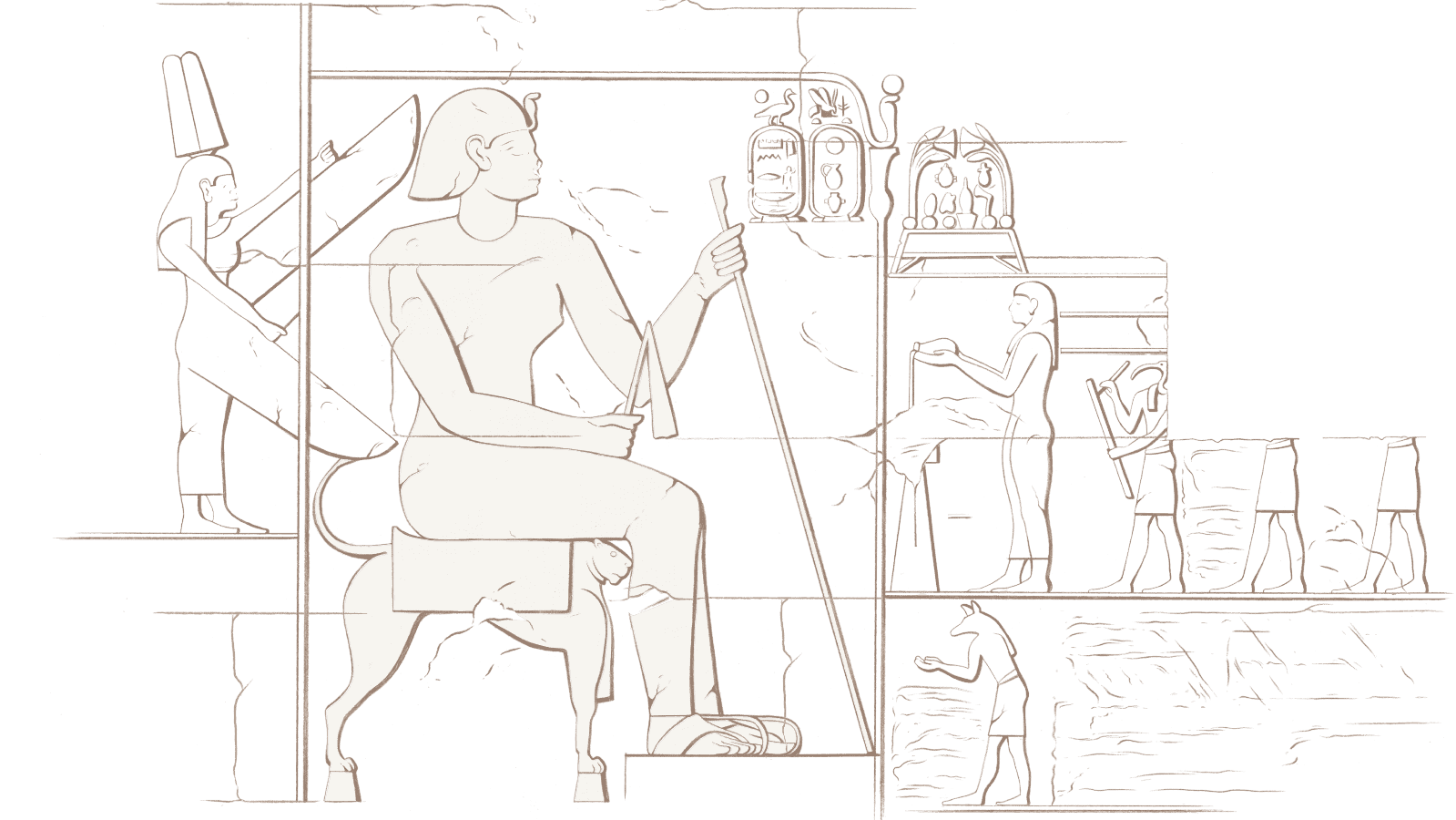

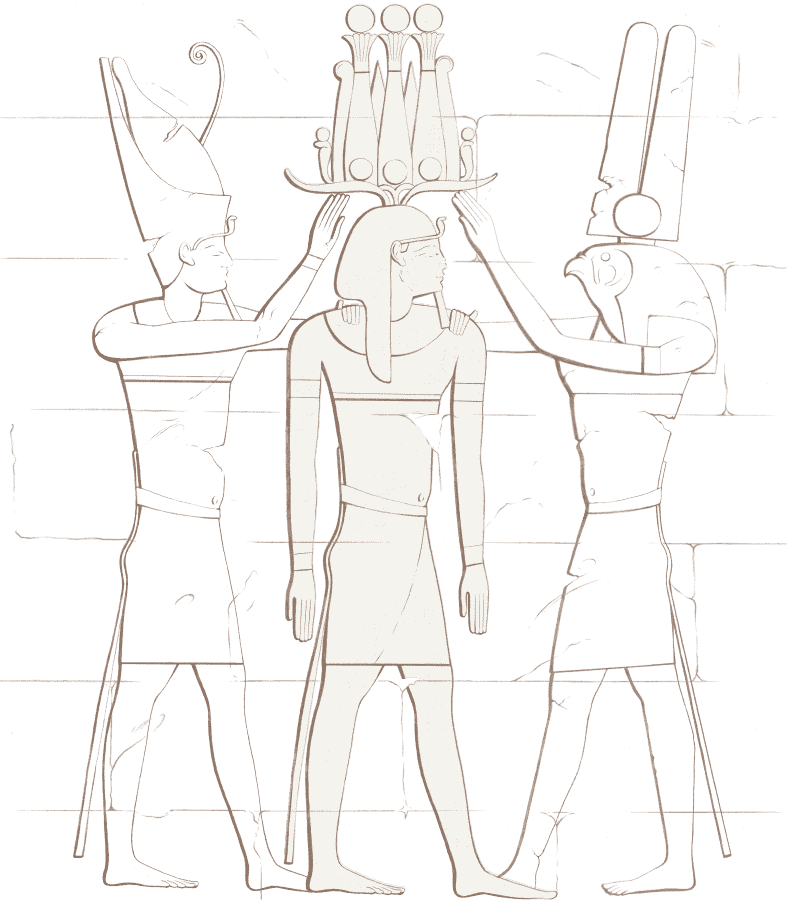

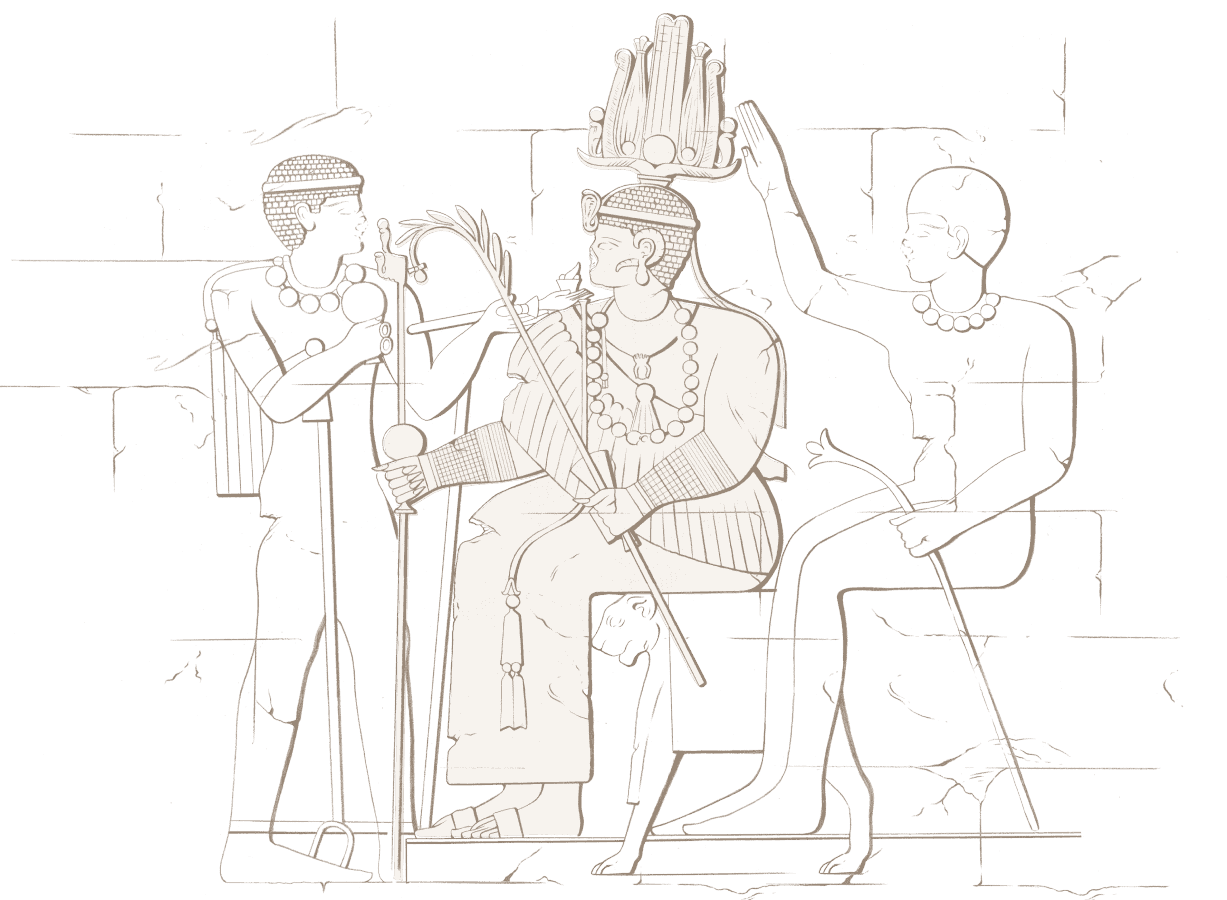

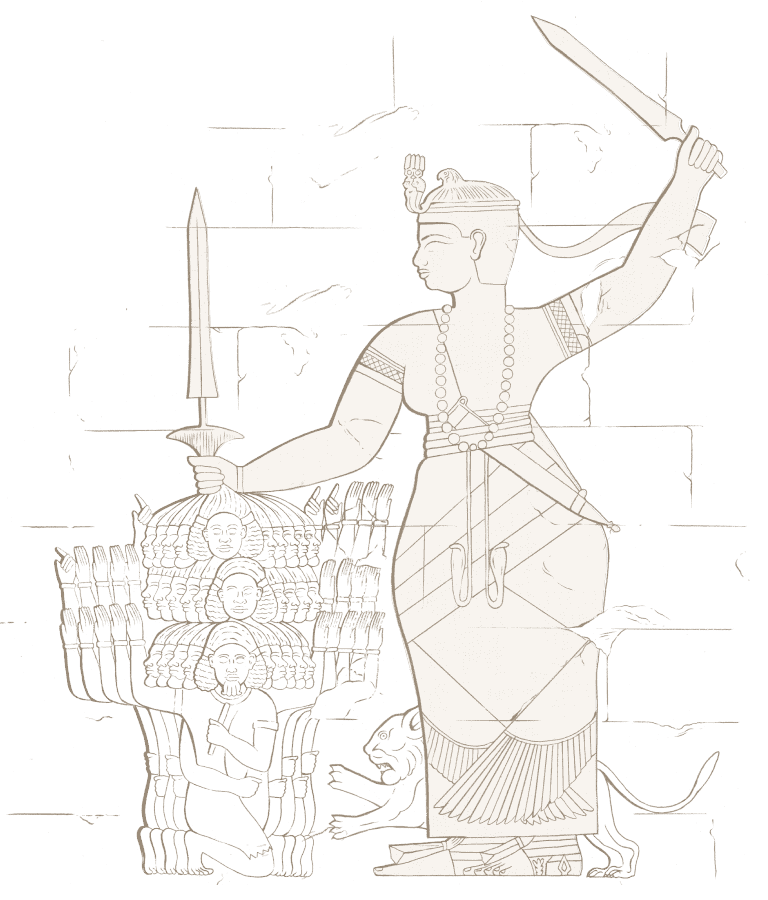

Kings

and Queens

Kings with the same name, and opposite views on Kushite culture. Queens that led armies and ruled their kingdoms alone. These are only a few of Meroë’s many rulers.

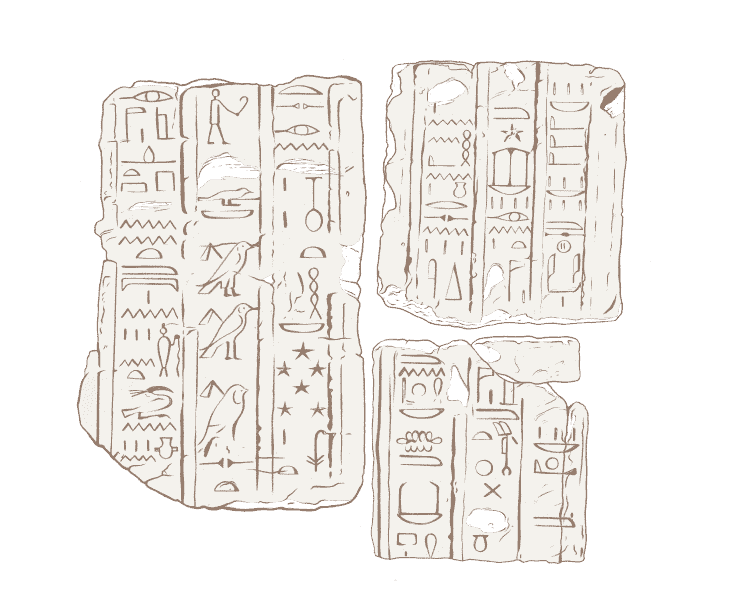

A lot of our knowledge on Meroë is based on the writings of ancient Egyptians, Romans and Greeks (which is biased and could be untrue). This is because we don’t fully understand the Meroitic language. There were two forms – cursive and hieroglyphic. Today, work continues to fully decipher the Meroitic language. One day this ancient civilisation may finally be able to tell its own story, in its own words.

Retrace the steps of the ancient Kushites by exploring its royal cemeteries on Street View.

Credits

In partnership with

This project was made possible thanks support from UNESCO Sudan and our expert historical advisors and fact-checkers – Dr Shadia Taha and Dr Khaled Elgawady.- Bonnet, C., 2019. The Black Kingdom of the Nile (Vol. 1000). Nathan I. Huggins Lectures.

- Kendall, T., 2007. Egypt and Nubia. Routledge.

-Welsby, D.A., 2001. Kendall, T., Kerma and the Kingdom of Kush, 2500–150 BC: The Archaeological Discovery of an Ancient Nubian Empire. Washington DC: National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1997, 6. Africa, 71(2), pp.316–317.

- Taha, S., 2020, What did the Kushite Empire do for Ancient Egypt? 25 September. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D8a0w_ZbP2Y (Accessed: 15 September 2021).

- Taha, S., 2020, Did the invasion of the Kingdom of Meroe take place? 30 October. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7jGh9iKFcOc (Accessed: 15 September 2021).

- Taha, S., 2021, The power of Kerma: Exposing facts erased by ancient Egyptians: Part 1. 14 February. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aV0CZI-Y3_c (Accessed: 15 September 2021).

- Taha, S., 2021, The power of Kerma: Exposing facts erased by ancient Egyptians: Part 2. 14 February. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vmfFpCdrNTs (Accessed: 15 September 2021).

- Taha, S., 2021, Queens and High Priestess: Women in ancient Kush: Part 1. 14 September. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WiLNUYC-g4k (Accessed: 15 September 2021).

- Taha, S., 2021, Queens and High Priestess: Women in ancient Kush: Part 2. 14 September. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_16tSlJxIio (Accessed: 15 September 2021).

- Fluehr-Lobban, C., 1998, August. Nubian Queens in the Nile Valley and Afro-Asiatic cultural history. In Ninth International Conference for Nubian Studies.

- Williams, L. and Finch, C.S., 1984. The Great Queens of Ethiopia. Black Women in Antiquity, pp.12–35.

- Welsby, D. A., 1996. The Kingdom of Kush: The Napatan and Meroitic Empires. Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers, 1996.

- Török, L., 2018. Nubians move from the margins to the centre of their history. From the Fjords to the Nile: Essays in honour of Richard Holton Pierce on his 80th birthday. Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology, pp.1–18.

- Török, L., 1997. The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Brill.

- Adams, W.Y., 1994. Castle-houses of Late Medieval Nubia. Archéologie du Nil Moyen, 6, pp.11–46.

- Griffith, S., 2015. Offerings to the god Osiris found hidden beneath ancient Sudanese pyramids: 2,000-year-old structures marked Kushite graves. Daily Mail Online, Science and Technology, 15 September. Available at https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-3239899/Pyramids-discovered-ancient-Sudanese-cemetery-2-000-year-old-structures-built-dead-hid-offerings-god-Osiris.html (Accessed: 15 September 2021).

- Owen, J., 2013. 35 Ancient Pyramids Discovered in Sudan Necropolis. LiveScience, 6 February. Available at https://www.livescience.com/26903-35-ancient-pyramids-sudan.html (Accessed: 15 September 2021).

- Owen, J., 2013. In Photos: Beautiful Pyramids of Sudan. LiveScience, 6 February. Available at https://www.livescience.com/26900-ancient-pyramids-sudan.html (Accessed: 15 September 2021).

- Owen, J., 2015. 16 Pyramids Discovered in Ancient Cemetery. LiveScience, 16 September. Available at https://www.livescience.com/52186-16-pyramids-discovered-ancient-cemetery.html (Accessed: 15 September 2021).

-Dr Salah Mohamed Ahmed (pers comm) August 2021. Former Director of Sudan Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM), Director of the Qatar Archaeological Project in Sudan.

- Hinkel, F. W., 1992. Preservation and Restoration of Monuments. Causes of Deterioration and Measures for Protection, in C. Bonnet (ed.), Études Nubiennes I. Actes du VIIe Congrès international d’études nubiennes, 3–8 Septembre 1990. Genève, pp.147–185.

- Hinkel, F. W., 2000. The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. Architecture, Construction and Reconstruction of a Sacred Landscape, Sudan & Nubia, 4, pp.11–26.

- Wolf, P., Riedel, A., Bashir, M.S., Yellin, J.W., Hadlof, J. and Büchner, S., 2018. The Qatari Mission for the Pyramids of Sudan: Fieldwork at the Meroe Royal Cemeteries: a progress report. Sudan & Nubia, 22, pp.3–28.

- Wolf, P., Riedel, A., Bashir, M.S., Yellin, J.W., Hadlof, J. and Büchner, S., 2014. The Qatari Mission for the Pyramids of Sudan. – Fieldwork at the Meroe Royal Cemeteries – A Progress report. Bashir, M.S. and DAI, A.R., Kirwan Memorial Lecture.

- Vincent, F., 2012. Preparing for the Afterlife in the Provinces of Meroe. Sudan & Nubia, 16, pp.p-52.

- Bonnet, C., 2020. The Cities of Kerma and Pnubs-Dokki Gel. The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia, p.201.

- Bonnet, C., 1992. Excavations at the Nubian Royal Town of Kerma: 1975–91. Antiquity, 66(252), pp.611–625.

- Taha, S., ‘Frankincense: Traditions rooted in the Sudanese DNA’ in proceedings of the Red Sea VIII International Conference on the Peoples of the Sea Region and their Environment, held at The Polish Centre for Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw, 4–9 July 2017.

- Haaland, R., 2014. The Meroitic Empire: Trade and Cultural Influences in an Indian Ocean Context. African Archaeological Review, 31(4), pp.649–673.

- Bashier, N.H., 2014. The ancient trade routes of the Meroitic Kingdom with the countries of the Mediterranean. RUDN Journal of World History, (1), pp.92–99.

- Davis, S.L., Roberts, C. and Batkin-Hall, J., 2018. A comprehensive approach to conservation of ancient graffiti at El Kurru, Sudan. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, 57(1–2), pp.1–18.

- Helmbold-Doyé, J., 2019. Tomb Architecture and Burial Custom of the Elite During the Meroitic Phase in the Kingdom of Kush. In the Handbook of Ancient Nubia (pp.783–810). De Gruyter.

- Rilly, C. and de Voogt, A., 2012. The Meroitic Language and Writing System. Cambridge University Press.

- Adams, W.Y., 1994 – ‘Big Mama at Meroë: Fact and Fancy in the Candace Tradition.’ Paper presented at the Third International Conference of the Sudan Studies Association, Boston.

- Fluehr-Lobban, C., 1998. Nubian Queens in the Nile Valley and Afro-Asiatic cultural history. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

- Carney, E.D. and Müller, S. eds., 2020. The Routledge Companion to Women and Monarchy in the Ancient Mediterranean World. Routledge.

- Lobban Jr, R.A., 2021. Historical Dictionary of Ancient Nubia. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

-Matić, U., 2014. Headhunting on the Roman Frontier: (Dis)respect, Mockery, Magic and the Head of Augustus from Meroe. The Edges of the Roman World, pp.117–134.

- Lohwasser, A., 2020. The Role and Status of Royal Women in Kush. In The Routledge Companion to Women and Monarchy in the Ancient Mediterranean World (pp.61–72). Routledge.

- Hakem, A.A., 1981. The Civilisation of Napata and Meroe. General History of Africa II, p.298.

- Trigger, B.G. and Heyler, A., 1970. The Meroitic Funerary Inscriptions from Arminna West. Publications of the Pennsylvania-Yale Expedition to Egypt.

- Griffith, F.L., 1917. Meroitic Studies IV. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 4(1), pp.159–173.

- Griffith, F.L., 1916. Meroitic Studies. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 3(1), pp.111–124.

- Haycock, B.G., 1972. Landmarks in Cushite History. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 58(1), pp.225–244.

- Haycock, B.G., 1967. The Later Phases of Meroitic Civilisation. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 53(1), pp.107–120.

- Baldi, M., 2015. Isis in Kush, a Nubian Soul for an Egyptian Goddess. Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Archaeology, (02), pp.97–121.

- Winters, C., 2005. Meroitic religion. Arkamani Sudan Electronic Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology.

- Ahmed Hussein Abdelrahman Adam (Pers Comm) August 2021. Associate Professor, University of Khartoum, Department of Archaeology.

- Wenig, S., 1975. ‘Meroe, Geschichte des Reiches’, „Kunst’, „Schrift und Sprache’, in Lexikon der Ägyptologie, 4, pp.98–107.

- Wenig, S., 1975. ‘Ergemenes’, in Lexikon der Ägyptologie, 1, p.1266.

- Wenig, S., 1975. ‘Amanishakhete’, in Lexikon der Ägyptologie, 4, pp.170–171.

- Wenig, S., 1967. Mitteilungen des Instituts für Orientforschungen, 13.

- Lohwasser, A., 2013. Die meroitische Periode des Reiches von Kusch, in Wenig, S. and Zibelius-Cheen, K., Die Kulturen Nubiens – ein afrikanisches Vermächtnis, Dettelbach, pp.227–244.

- Chapman, S. and Dunham, D., 1952. Decorated Chapels of the Meroitic Pyramids at Meroe and Barkal. The Royal Cemeteries of Kush (RCK), 1–3, Boston.

-Dunham, D., 1957. Royal Cemeteries of Kush: Royal Tombs of Meroe and Barkal. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Dunham, D., 1963. The West and South Cemeteries at Meroe. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Porter, B. and Moss, R.L.B., 1952. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphics Texts, Reliefs and Paintings, VI. Nubia, The Deserts and Outside Egypt. Meroe Pyramids, pp.241–260. References for Scenes from the Pyramid of Ergemenes: p.257.

- Lepsius, R., 1849. Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopien. Nicolaische Buchhandlung, Berlin, Edition des Belles Lettres, Geneve 1972–1973, 12.